Tubberneering Tannery

It may be difficult for people today to understand how and why a Tannery (Tan Yard) existed in Tubberneering Upper in the 1800s. The understanding comes from an appreciation of rural life at that time when communities had to be self-sufficient in almost every aspect of their lives. The Tan Yard produced valuable leather products which were essential for everyday life such as harnesses, shoes, boots, clothing, bags, machinery belts and many other products.

The Tannery at Tubberneering Upper nestles neatly by the bank of the Bracken river in a field on the southern edge of the farm of local man, Thomas Hill. It is a secluded and remote setting with a haunting atmosphere, where the buildings and surrounding features are waiting to tell their story to anyone who visits.

According to Thomas Hill, the industry was a thriving family business during the 1800s. He remembers his uncle, who was born in the late 1890s, reminiscing about the Tannery from his memories as a very young boy on the farm. The Tannery appears to have ceased operations around the turn of the 20th century. This would be in keeping with the timeline for closure of many rural Tanneries at that time when leather could be imported cheaper from the United States than it could be produced in Ireland.

Tan Yard Buildings

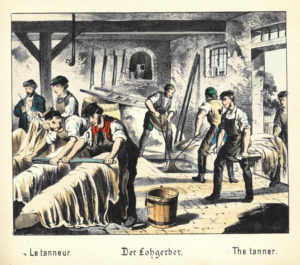

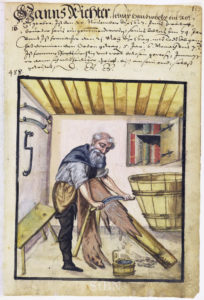

Early tanneries generally consisted of a couple of buildings including a covered shed for storing and grinding the oak bark and a separate building for fleshing, tanning, and working the hides.

Tanneries often operated only during summer months in the early 1800s when almost all the work was carried out in the open. By the mid-1800s, a typical Tan Yard operated all year round inside a large, sometimes heated, building.

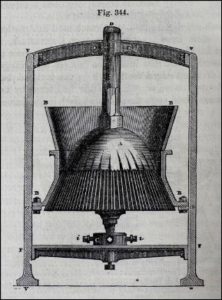

Upon visiting the Tan Yard at Tubberneering Upper it was, as expected, found to consist of two buildings as indicated on the OSI Map of 1837-1842 (see below). The first building housed the bark mill and featured an outward curve in the wall on both its southern and northern walls. This was to facilitate the circular path of the horse as it ‘drove’ the bark mill.

The second building was most likely where the fleshing and working of hides took place. At this tannery, the tanning process itself took place in the stone vats outside of the buildings.

OSI Map showing Tubberneering Tan Yard

The location of the Tan Yard at Tubberneering Upper is circled in the screen shot of the OSI Map of 1837-1842 below. The importance of the Tan Yard’s proximity to the river will be evident when you read further about the process that took place at the Tannery.

© Ordnance Survey Ireland/Government of Ireland – Copyright Permit No. MP 005821

What is Tanning

Tanning is the process of treating animal skins and hides to produce leather. The place where this process takes place is a Tannery or Tan Yard. The process involves permanently altering the protein structure of the animal skin, making it more durable and less susceptible to decomposition. The Irish name for a Tanner was Súdaire and this word still exists to the present day.

The manufacture of leather was far from a straightforward process and would have required a commitment to hard physical work along with a strong constitution due to the nature of the work involved.

The Tanning Process - Learn More

Skins arrived at the Tan Yard from the local butchers by horse and cart. The access road to the Tan Yard at Tubberneering Upper was at the back of the farmhouse and stretched approximately 100 metres down to the Bracken river at the southern edge of the farm.

If the skins arrived salted and dried, the Tanner would re-hydrate them by soaking them in water to wash out the salt.

At Tubberneering Upper, this would have been carried out by soaking the skins in vats or suspending them in the flowing water of the Bracken River. There is evidence of what a appears to be a ‘Water Race’ at the tannery which would have been very useful for several stages of the tanning process, including the initial soaking of skins.

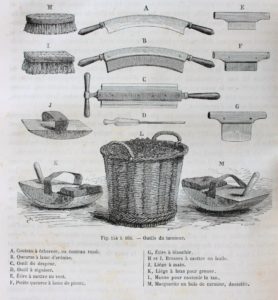

After the rehydration process was complete, the animal hides were scraped on a fleshing beam (log or board) to eliminate all traces of fat and flesh, and subsequently soaked for 1-2 weeks in a caustic lime solution to remove the hair or fur. Before the availability of lime, Tanneries used a homemade lye solution, prepared by mixing wood ashes with water. Some early tanneries collected urine which they added to the lye solution to help with the removal of hair from the hides. Lime was more readily available by the mid-1800s and replaced the lye solution. It was during this soaking stage that rotting of living tissue took place resulting in the Tan Yard emitting a significant stench.

The location of the Tan Yard at Tubberneering Upper would have been chosen for its proximity to the river. However, it was also fortuitous that it was at the extreme edge of the boundary of the farm, well away from the farm house so that the stench might not impact on the householders too much.

After soaking the hides in the lye or lime water, the workers rinsed them, then stretched them over a large log and used a fleshing knife, called Shiguers, to remove the hair. Removing the hair was hard work. A side industry of the Tannery involved collecting the hair that was removed during this process and selling it to plasterers. The hair improved the adherence of plaster to a wall and prevented the plaster from cracking. It is not known if this practice took place at this tannery.

After scraping off all the hair, the hides were placed into running water for several days to wash out any remaining lye. During this washing process, the hides were turned regularly to ensure that all the lye was removed. Once this thorough washing was complete, the hides were put into stone vats which were then filled with water saturated with tannin obtained from the oak bark.

The tanning bark was harvested from actively growing oak trees in the spring. The workers used tools like crowbars to peel the bark from the trees. The bark was then flattened, ground, dried, and then sold to the Tannery. In many tanneries, like at Tubberneering Upper, the bark was ground on site by a bark mill driven by an animal, most likely a horse or donkey.

There is no record of where the oak bark required for the Tan Yard in Tubberneering was obtained. It is possible that it, like the Tannery at Ballycanew, came from the Earl of Courtown’s estate. According to Thomas Hill, family lore suggests it may have been sourced from Courtfoyle Estate in County Wicklow.

Next came the actual tanning process. A layer of crushed bark would be put in the bottom of a stone vat and covered with water. A layer of hides was added on top and followed with another covering layer of bark. This process was repeated until the vat was filled to the brim. The hides were left soaking like this for several weeks and then washed in running water for a week or more.

The hides were then allowed to dry during which time the workers added oil to the hide to soften them and, where the product demanded it, used colour treatments.

Did you know?

The English word for Tanning is from the Latin word Tannum (oak bark). The oak bark was known in Irish as Coirtech.

'Tan Yard' related old English phrases

- Piss Poor

Leather tanneries regularly used urine in the tanning process. In some very poor families, everyone used to ‘pee in a pot’ and then sold the urine to the tannery. If your family had to do this to survive you were called “Piss Poor”. - Doesn’t have a pot to piss in

This meant that your family was worse than ‘piss poor’ because they, literally, did not even have a pot to piss in to carry their urine to the tanneries. - A Pure Finder

A Pure Finder had the less than desirable job of collecting dog faeces from the streets of towns and cities to sell to tanners, who used it in the leather-making process. Dog poop was known as “pure” because it was used to purify the leather and make the tough leather fibres more flexible. Pure collectors could be found where stray dogs gathered, collecting the poop which they kept in covered buckets. Some pure finders wore gloves, but most did not as it was easier to keep their hand clean than their glove.